[ad_1]

The rainbow is born from a deviation, from a sunbeam that breaks down and changes the angle of its trajectory. After this deviation, wavelength ranges are created, fragments of light that the human eye is capable of perceiving and translating into a specific tonality. Socorro Rosario Sicay’s eye is very accomplished in that, in different colors, to later be able to capture them on cotton. With coconut bark is made the beigeyellow with chamomile, violet with beetroot, orange with carrot… Sicay has based his entire life on that: recovering the Mayan traditions of women weavers in Guatemala, and keeping them alive, even though, on occasions, there have been I had to risk my life.

“I don’t study for a year, not for a moment, not for a second.” Sicay did not go to school, everything he learned he learned from his grandmother, Rosario, and from her mother, Dominga, who died at the age of 107. Through the Association of Women in Botanical Colors, which she chairs, she has been sharing that knowledge for decades.

They took me. All hooded. They took me, I had a swelling on my face and she had my baby, she was eight months old. They went to kill people. They came to lose our culture

rosario sicay

The association is on a narrow, shady street, among the helpers of low cement buildings, in San Juan La Laguna, and among the towns that surround Lake Atitlán. There are more than a dozen towns in western Guatemala surrounding that lake, Atitlán, which in Nahuatl means “between the waters.” The main tourist destinations are those located in the north: San Pedro, San Juan, San Pablo and San Marcos (all with the last name La Laguna and all with the names of Christian apostles, in a predominantly Tzʼutujil Mayan area).

The association also has a store full of huipiles and other traditional dresses, notebooks covered with cloth, scarves, shirts, many photos on the walls, and a poster that says that the constitutional president of the Republic of Guatemala, Óscar Berger, granted in 2004 the “National Order of Cultural Heritage of Guatemala to the Mayan weaver woman Socorro Sicay for her extraordinary contribution to one of the authentically national expressions such as the production of textiles and its meaning in the Mayan worldview.”

“I went through a great crisis in 1982, when the army took me. They wanted to kill me for rescuing this Guatemalan tradition. They said that we are guerrillas, but that is not the case, we are fighting, hard-working and enterprising women”, recalls Sicay. With these words, she refers to one of the harshest periods of extermination against the indigenous communities in Guatemala. It was the time of the dictator José Efraín Ríos Montt, who in 2013 was sentenced to 80 years in prison for genocide and crimes against humanity, perpetrated between 1982 and 1983.

“They killed my husband. His name was Nicholas. In 1982, during the massacre, when they wanted to kill me. Their names were Ventura and Cuixulic and Chepe and Juanito [quienes mataron a su marido]. Only one is alive, Ventura. I’m not afraid to say it. They took me. All hooded. They took me, I had a swelling on my face and she had my baby, she was eight months old. They went to kill people. They came to lose our culture”, he specified. The dictator Ríos Montt was in power for only 17 months, but in that time he massacred more than 10,000 people, mostly Mayan peasants. Hundreds of villages were also razed, according to the CIDOB research center in Barcelona. It was one of the most violent episodes of the civil war in Guatemala, which between 1960 and 1996 claimed the lives of thousands of people.

Socorro did not go to school, everything she learned, she learned from her grandmother, Rosario, and from her mother, Dominga, who died at the age of 107.

“I tell God, when I meet him on the street, ‘that’s a bad man.’ I can’t accuse him. When they called us and gave people money, they didn’t give me the money. I presented all my papers, but they did not receive me, ”he laments. Sicay talks about the financial compensation from the Government, which never reached her. But despite everything, she carries on with her association, weaving to remember, so that the traditions of her culture are never forgotten.

“I am teaching the ladies so they can learn. All designs come from my head. We are a group of 30 women, in the cooperative. The active ones are widowed women.

He also wants to sense young kids “so they don’t fall for drugs,” he says. And he gives them work by sending them to the forest to collect coconut, banana, and zapote bark. This bark is cooked and then ground and is also used to obtain different colors.

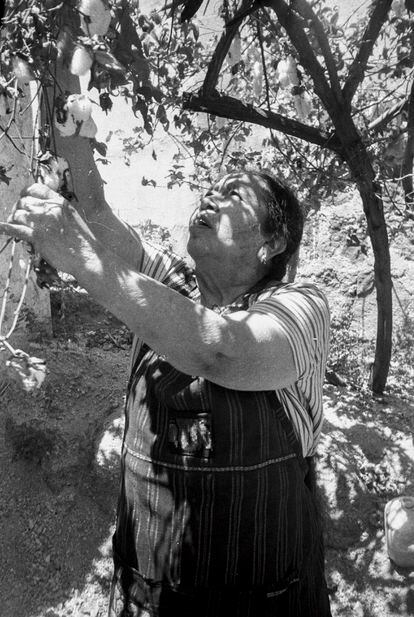

Very close to the store there is another store with samples of everything they make from plants and bark and shrubs and vegetables. Socorro sits behind a table and shows how he turns piles of Ixcaco cotton, very characteristic of the area, into fine threads, and then into skeins. She then gets up, she goes to the wall on the left, where she hangs a panel with photos, and points to it.

“I went to spin cotton in Canada. I went to Vancouver, Toronto and Victoria, Montreal, St. Kitts, Manatoba.” She traveled there so that the Canadian indigenous women could teach her how they weaved and she would tell them how they did it in Guatemala. An exchange of knowledge. Although it was much more than that: “I tried everything. I drove, they taught me to drive, ”he says while pointing to a photo of her on the ceiling where she is seen driving a golf cart. Nearby are other images where she is stepping on snow. Until then she had never seen snow. He points to it, laughs, and this woman who continues to protect traditional Guatemalan crafts says: “I received it with my mouth and she thanked God very much.”

You can follow PLANETA FUTURO on Twitter, Facebook my instagramand scribble here to our newsletter.

[ad_2]